On imagination

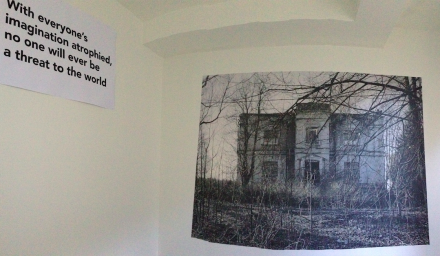

THE EXHIBITION by Pavel Matveyev at Cigarrvägen 13, Stockholm, is titled “With everyone’s imagination atrophied, no one will ever be a threat to the world #3.” A complex and though-provoking title presents a very simple installation of one large scale photographic image to be viewed from an armchair, with headphones of a soundscape, an audio documentation from the same site.

The image he chose was of an abandoned manor house on the outskirts of Moscow. The house was originally an aristocratic palace, but like many buildings of its kind, was converted into a public institution during Soviet times. After the revolution, properties that weren’t converted into sanatoriums or hospitals fell into disrepair. And in turn, those institutions have long since been abandoned.

The specific history of this house, although uncertain, calls into a questioning of what history and cultural identity means in the post-soviet era. Without a ‘golden age’ to fall back upon, how can these fading, decrepit romantic visions be anything more than documents of catastrophe? What image of ‘culture’ can be salvaged from history to remain relevant to today and moving forward? The manor house is viewed through an entanglement of overgrown branches. Dead wood obscuring the view a once splendid, great culture? Or a new, neural network emerging out of the ruins? Maybe both.

The most interesting part of the exhibition is not the image by itself, or image as art, but the decision by the artist to merely wallpaper the gallery with the image and guide the viewer to be seated in a comfortable old-fashioned armchair, to view the work whilst listening to an audio sample taken from the site. The work becomes temporal and highly evocative as you are emerged in the soundscape and the blown up patterns. You can hear and feel that this is a documentary of an abandoned space as you are surrounded by the rustling of leaves and the feint sound of dogs barking in the distance. It is a catastrophe that has happened. It is too late. You wait for a narrative or voice to appear, some semblance of human presence, but it never does. The audio is on a 3-minute loop, offering no answers and no conclusions.

You almost start to hallucinate traces of human life. Can you hear voices or music in the background or is that sound from outside the gallery, the here and now seeping in through the corners? For a few minutes you are thrown into a powerful drama in this space. But it is emotion observed, not filtered, emotion filled with gentle acceptance.

Elena Fanailova describes Matveyev’s work as a contemplation of the “post-Soviet, post-cultural, post-historic space devoid of emotive meaning.” But the work itself is far from lacking in emotion: you are caught somewhere between a photograph, a still image and a film you once saw. It’s like watching a Tarkovsky film for the first time, but even that analogy is far too obvious. When so much of our consumption of images, still and moving, happens in the digital realm, this is a space in between, a ‘Russian’ sensibility in exile. You are a foreigner to the experience but complicit in it. Fanailova writes: “There is no pity, no nostalgia, only the purity of observation: photography and sound. This is post-history, post-culture, post-game.”

Whether this is a questioning of a image-making, a nostalgic longing for a meaningful contemporary cultural identity, or a personal coming-to-terms-with-history, Matveyev captures your heart through your senses with a sensitive and elegant intervention. He swiftly avoids the work becoming bombastic or clichéd by merely pointing us to experience an image in a new way again. It’s optimistic: your imagination is not atrophied; it just needs to be awakened gently. Matveyev’s exhibition is a commentary on all the consumption of all ‘culture’, bringing into question the relentless flow of images we experience on a daily basis in bite-sized packages of ‘history.’ Imagination is not dead or atrophied. But we must understand that images contain a tremendous power to influence on the way we think. They direct our awareness, and by doing so, shape our world view and our collective memory -no matter who we are or where we are from.

About the artist

Pavel graduated from Moscow State University’s faculty of journalism in 2002, and in 2006-2007 studied photography at the University of Brighton, UK. In 2012 he received his Master’s degree in Fine Arts from Konstfack in Sweden, where he is now a permanent resident.

In his work Pavel Matveyev explores connections between the private and the public, reflecting on nostalgia, melancholy and the luxury of boredom, often investigating notions of the gaze and the poetic image. In this process he employs simple tools in the form of photographic and audio recordings. His works are held in private collections in Sweden, UK, France, Norway and Russia and he has exhibited at Konstfack, Gävle konstcentrum and Arkitekturmuseet, Stockholm.

About the space

Cigarrvägen 13 is a 30-square-metre art space run by Stockholm-based artists Ami Kohara, Frida Krohn, Ylva Trapp, Johan Wahlgren, Helena Piippo Larsson, Maryam Fanni and Lisa Renvall. Together they form an artists collective who aim to make it easier for all types of local artists to exhibit their work. Cigarrvägen 13 has been opened with support of Stockholms stad.