Things you cannot design

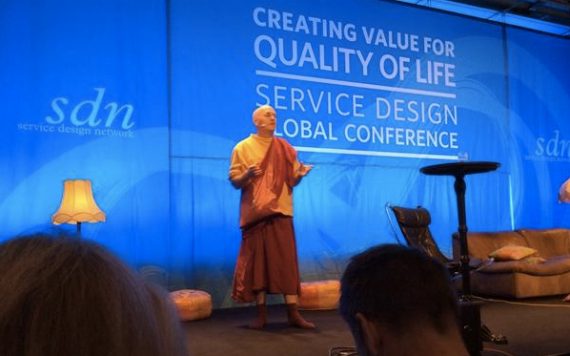

THE ARTIST-MONK Tenzin Shenyen spoke at a Service Design Network conference in Stockholm in 2014.

Shenyen is the Tibetan word for friend. And Tenzin Shenyen is a British-born Tibetan Buddhist monk who received his monk’s vows from His Holiness the Dalai Lama in July 2004.

Shenyen has spent the decade or so wandering around the world, and as he describes it, “Allowing the blessing of the tradition to mingle with the secular beauties of my own culture.” His office consists of a rolled-up copy of Artforum and an old Nokia 100. He thinks he can be contacted via his blog radioshenyen, but he’s not always sure.

A while back, I managed to reach him just before he left a monastery and Buddhist university in Thailand, where he had been teaching for a year. I asked if he would answer a few questions for the online magazine The Forumist.

“Send me a few questions,” he said. “But be warned – I only answer questions that are both logical and beautiful.”

A conversation with Shenyen always helps to refresh your outlook on life and introduce a new perspective to your own worn-out conclusions. His writings and talks often remind us about the continuously changing nature of life – that karma and experience cannot be correlated for predictable effect, much less be designed.

Here is the interview that was published by The Forumist:

What is spirituality?

“Answer #1

A teacher once asked, ‘How do you know what a candle is when you haven’t seen all the candles in the world?’ If he had said ‘electronic devices’, the question would be easier to imagine, to relate to, but… candles? Can’t I at least be sure about what a candle is?

“Buddhist philosophy operates in that space – the space of not-knowing. And this not-knowing is the basis – the grammar – of spirituality in Buddhism. So, likewise, I want to say ‘I don’t know’ to your question, not as an answer but as one of many possible responses. How can I possibly say what spirituality is when I haven’t ‘seen’ all the spiritualties in the world?

“Answer #2

Spirituality is communion with The Invisibles. It is a relationship with that which closes your physical eyes. These closed eyes can be faked, or ritualistically assumed, or genuine. Only the latter is true spirituality. It is being open to the idea that existence is not just ‘us and the animals’ within a cold dark universe. This openness begins in discipline, then acquires dignity and presence, then dissolves into grace and abandon. By discipline I mean sustained acts of faith and imagination.

“Answer #3

‘A love? I love your father, certain black Madonnas from Africa, the flowers which grow by the Atlantic, difficult texts… and you.’ From The Samurai by Julia Kristeva.”

What is the hardest part of your practice for you personally?

“The hardest part of my practice is remaining homeless and jobless while back in the West. I yearn for something bigger – and gentler(!) – than a tent to live in. Living as a homeless monk back in the West is a really powerful experience psychologically. It is an exercise in trust and in realising the nothingness[ITALS] of my life, but it is physically demanding and unfeasible beyond the summer months. So I’m beginning to think in terms of it as finding a part-time job or room somewhere. I’ve lived in western monasteries but they often feel kind of jaded or false. I’ve seen westerners become monks and then forget that they are the products of the most individualistic, high-speed societies that ever existed on the planet. They then try to squeeze themselves into an ancient Asian monastic model and it hardly ever works. It is easy to become listless and dull, emotionally starved and alienated from your own cultural roots and personal histories. This is not renunciation – it is a loss of nerve and a form of living in denial.”

You made a conscious decision to not be attached to one home for quite a few years. What was that experience like?

“It wasn’t a ‘conscious decision’ so much as a pragmatic one. I was heading back to England after 11 years in Asia, I was a monk and wasn’t supposed to be looking for work or have a home. So I… just knew I was going to be homeless. And I just went with that reality. I accepted it – quite naively, actually, I would say. I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for. I bought a tent in London and then decided to wander in England. I thought, ‘Where’s the safest place to go?’ And I headed towards Cornwall. I’d never put a tent up before in my life and suddenly I was in this farmer’s field outside Plymouth, without permission, in the dark.

“That year I slept in 93 different places – I wandered through Cornwall for a few months and then catapulted to Japan to do a 1,100km pilgrimage. I learnt so much about just trusting in situations. And also about how decisions often cannot be made until one is in the midst of the ‘landscape of answer’. The places I slept in, I simply couldn’t have planned it all out in advance. I had to be walking in the dark and tired and looking around me – in the landscape of answer. Being homeless in the UK as a monk is a ‘dual nationality’ kind of thing – you’re semi criminal, as wild camping is illegal, and at the same time you’re the epitome of trustworthiness – I wear my robes. I guess it helps being a monk from Liverpool in this respect!”

What kind of practices or concrete behaviours would you recommend to any lay person – ‘non-medical antidepressants’?

“Concrete behaviour – and concrete evidence – is only one dimension to Buddhist practice. There is also ‘water’ behaviour, ‘air’ behaviour, ‘time-lapse’ behaviour, etc. For example, mindfulness practice has now entered the mainstream as a secular practice devoid of any religious dimension. And this is fine. Buddhism doesn’t own the copyright on mindfulness. But these ‘new’ approaches, such as MBCT (mindfulness based cognitive therapy) or MBSR (mindfulness based stress reduction) lack the existential vastness of Buddhist philosophy and cosmography.

The modern secular forms really just deal with a kind of ‘local’ problem and ignore the vaster existential problem – you reduce stress created by your workplace in order to… return to work and more stress. It is essentially nihilistic. Whereas, in Buddhism, you are practising in order to end all forms of suffering forever, to transcend having to have this kind of suffering body, even. Buddhism combines precise technique with existential vastness, and this dual flavour is where its power lies. Buddhism isn’t interested in changing the molecular structure of the brain – a bullet or cocaine can do that. It is interested in changing karma – the moment-by-moment presencing of reality – this is something that science can’t get a handle on.

“But bearing in mind what I said in my previous answer – about the dangers of just superstitiously adopting wholesale an alien culture – I would like to see people explore the existential practices of Buddhism and take them into contemporary settings.

“My personal ‘Buddhist universe’ is a scattergun intermingling of Madhyamaka, cinema, ritual practice, communion with The Invisibles, ethics, architecture, Instagram, purification practices, #verysimpledecisionmaking, #onehomeayear, silence, high-speed-super-slow, contemporary art, study as one of the healing arts – the list is potentially endless.