8: ON KNOWLEDGE

Podcast episode 8: ON KNOWLEDGE

Intro: Welcome to Nordic By Nature, a podcast on ecology today inspired by the Norwegian Philosopher Arne Naess, who coined the term Deep Ecology.

This episode, ON KNOWLEDGE, features two guests who have dedicated their life’s work to enabling marginalised communities protect their own resilience, whilst net-working and lobbying for policy changes around the issue of Food and Nutrition Security, Climate Change, Sustainable Livelihoods, and integrating People’s knowledge into bioregional development.

But first you will hear a few words from my colleague Ajay Rastogi, at the Foundation for the Contemplation of Nature. Ajay works closely with the women of Majkhali village in foothills of the Himalayas, in Uttrakahand, India. He set up the Vrikshalaya Centre there to be a meeting place and knowledge hub for the villagers and other communities in the Himalayan lowlands, as well as foreign visitors and homestay guests interested in more meaningful forms of sustainability.

We then hear from Nadia Bergamini who works at Bioversity International. Nadia also lives on and runs an organic, biodynamic farm together with her husband, in the countryside, outside of Rome.

At Bioversity International, Nadia collaborates with the Satoyama Initiative, helping communities all over the world develop strategies to strengthen their social and ecological resilience, and maintain the diversity of the landscapes’ agro-ecosystems, species and varieties.

You will then hear from Reetu Sogani, women’s rights activist who is working on strengthening and evolving Cultural and biological diversity, and its integration to address Food and Nutrition Security and build Climate Resilience, in the remote areas of Himalayas and other parts of India. Reetu has addressed the International Women’s Earth and Climate Summit in New York as one of the 100 women global leaders from across the world.

I hope you have time to sit back, relax and listen.

AJAY RASTOGI

I’m Ajay and calling in from Uttrakhand State. I have been a colleague of Reetu for last 7 years.

We have worked with the local small farmers here and we are aware of the beautiful work of Nadia at the Biodiversity International.

There is so much in the natural world that we are forgetting on a daily basis. The interconnectedness of the species and the knowledge systems within the landscape is something that’s getting diminished every minute, if we can say.

Close to 80 percent of all crop or food diversity is on the brink of extinction. Having said that, it’s a hope that is provided by the work of Nadia and of people like Rita who look at the policy level as well as at the grassroots level. The food cultures, the fibres for our making, our house for making our everyday life.

Things are also getting lost.

Ajay Rastogi at the Vrikshalaya Centre

The big question is, are we only thinking of biodiversity as food or are we thinking of it as a celebration of life? Each seed is life.

Somehow the work that we used to do with our own hands is considered a bit undignified at the moment. And that’s why the connection of the consumers with where the things are produced is getting longer and longer. And there is a certain level of disconnect.

That disconnect is not just about the value of the food. The nutrition of the food. But it’s also a disconnect about how those small farmers survive. What do they need? What is the kind of systems that we need to put in place in those landscapes so that the diversity could continue to flourish?

With the climate change, there is a lot under challenge.

Although the world is waking up at large to address the issue of climate change. But it is the resilience of the knowledge systems that we have for thousands of years. Developed in particular landscapes, those species, those varieties of crops which have survived these thousands of years of evolution in the particular landscapes, they are the ones which will really be the resilient species. And Reetu’s work, and also Nadia’s work speaks of that volumes about it in their experimentation, as well as in how the knowledge is being generated.

The beauty in their work is about experience learning. It’s something which has evolved and is done on the soil by hands together with the farming community.

Ajay Rastogi welcomes to the Vrikshalaya Himalayan centre, the home of the trees!

Often the argument is made that the lands are so fragmented and so small that the farming which can be supported in those lands will not be either viable for the livelihoods of the small farmers. And at the same time will not meet the scale that the growing human population needs to meet its food demands.

However, it seems very unlikely because what we have seen that when we grow diversity in smallholders’ farmers’ fields, there is much more energy production that takes place and much more diversity of food sources that we get out of it even now.

Although we may be claiming that the food culture has converted to industrial supplies and larger value chains of concentration where the food is processed and provided to the urban consumers through supermarkets, even there, if we see where is the production coming from, we find that more than 70 percent of the production is still dominated by small producers, which is being put together and processed.

And then we feel that the scale has been achieved. One of the farmers once mentioned to me and I have never forgotten that sentence. He said whosoever the person, maybe even the president of India, let us see. But he still has to eat three meals a day and that three meals I provide. So that is the level of respect that the small farmer deserves from all of us.

NADIA BERGAMINI

Hello, my name is Nadia Bergamini. And I work as a research specialist for Bioversity International in Rome.

Bioversity International is a Global Research for Development Organisation, ugh, and that is part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. And this group is a partnership of 15 different research centres that work for a food secure future, and these 15 centres collaborate with hundreds of partners across the whole globe.

Biodiversity International’s vision is to have agriculture biodiversity that nourishes people and sustains the planet. So, when we talk about agriculture biodiversity here, we intend the diversity of crops including the wild relatives, including trees, animals, but also microbes, and all the species that contribute to the production in agriculture.

Sound: meditation bell

Nadia Bergamini

On biodiversity

So, there’s a lot of diversity within an ecosystem. And we look at diversity from a species, but also from a genetic point of view. So, our mission instead is to deliver the scientific evidence, but also management practices, policy options in order to use and safeguard agriculture and tree biodiversity to attain sustainable global food and also nutrition security.

So basically, we work with the partners in many different countries around the world, mostly low-income countries where agriculture and tree biodiversity can actually contribute to improved nutrition, but also livelihoods, resilience and also productivity, and help in adaptation to climate change.

Usually these low-income countries are also the countries where we find most of the agricultural and tree biodiversity.

On collaboration for biodiversity

Since 2018 December 2018 we have been collaborating with another of these centres which is a Centre for Tropical Agriculture which is based in Cali in Colombia. And we have actually signed a memorandum of understanding to create an alliance. So, the two organisations will actually be working together much more strongly because we have very similar agenda and very similar mandates. So, we actually are going to complement the work of one Institute with the other.

So, this is sort of a future for us as well.

On the global challenge of staple foods and climate change

So why is the work that we do important because we know that the global population is growing, and we have predictions that say that by 2000 10 in 2050 we will be 9 million people in the world or even more. And this means that we need to feed all these people, and the food availability needs to actually expand in this especially in developing countries.

We actually facing a lot of global challenges like the challenge to reduce global malnutrition to adapt to climate change but also to increase as we said productivity and reduce risk, and also to address shrinking food diversity which is happening all over the world, and reduce the negative impacts of agricultural production on natural ecosystems.

And we think that production needs to focus on a diverse range of nutritious foods, which come from production systems that are highly biodiverse. We think that it’s better to increase their production in these type of systems rather than increase the volume of the few staple grains that presently cover 50 percent of the world’s energy intake.

And these grains are rice wheat and maize.

We are actually convinced that using on safeguarding agricultural and also tree biodiversity can help meet all these challenges.

And also, we know that farm households unruly corn wheat communities which are the people we work with have long since used agriculture and tree biodiversity to diversify their diets, to manage pests and disease, and also weather-related stress. The problem is that in the past policymakers and researchers have never considered these types of approaches as economically viable. Research has never gone into this direction or very marginally. But recent scientific evidence that has demonstrated that actually agriculture and tree biodiversity used in combination with novel technology, and also approaches, can offer a lot in addressing all these challenges.

It also brings increasing recognition as a tool to achieve a global sustainable development goals. which we’re all working towards.

On diverse, small-scale production

We work with agricultural biodiversity, so as I said, we promote small scale production that is highly diverse. So not only diverse in number of species that are that are cultivated, but it could be also diverse in the number of varieties of the same species.

For example, we work a lot with the farmers in Africa who cultivate beans. And what we have seen is that cultivating on the same field, different varieties of beans can actually reduce the impact of pests and diseases on the production systems.

So, we actually promoting genetically diverse systems because they actually much more adapted to climate change because they have a lot of more variety and there’s much more than great opportunity for some of the right varieties to perform well in different environmental conditions.

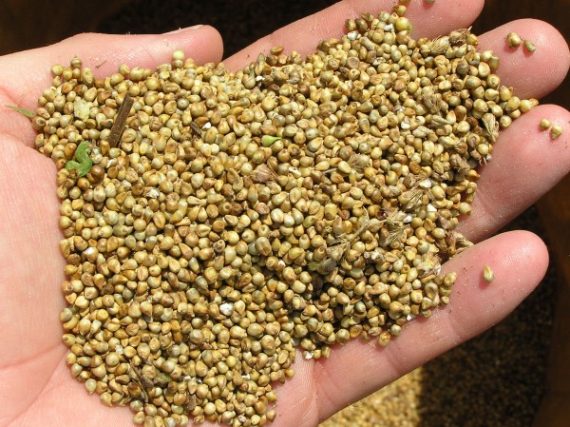

The promise of millet as a resilient crop

We work a lot also with university and research institutes in these countries. We also work in preparing university curricula on agro-biodiversity. For example, we have a big program on the so called the neglected and under-utilised species which Millet is one of these species.

What we have done in the projects working with the with these species is actually to show what are the advantages for the farmers to cultivate these species, because they are actually proven to be more adapted to marginal environments. So, for example in India we have been working with minor millets and some areas of India are really facing a lot of heat and drought problems. And we have seen that some of these minor millets are really adapted to these environments.

They can thrive under low input and stress stressful growing conditions, that usually limit the productivity of staple crops. And they’re also highly nutritious. So they can actually contribute to healthier diets. And they also have a lot of potential for development as novel consumer products because we also engage with local private sectors and try to find ways to make these produce more attractive to young to young people but also to adults creating new recipes and way of presenting millets, for example in cookies or other plates.

And also, it is important to conserve these neglected and under-utilised species because they are also linked with the local culture and traditions. We know that by strengthening the use of these conservation and the use of these species we are also strengthening local identities. And we also contributing to empower marginalised communities.

On local culture and women

Yes, we have a program on, on specifically on gender and trying to see the different roles that men and women play within the agricultural sector in especially in these low-income countries. And we have actually seen that although women often are not included in decision making. They actually play a very important role in managing farms. Women are usually engaged in cultivating the so-called home gardens and there where they usually select different varieties of medicinal plants but also condiments and which actually compliment a lot for the health and also for the diets of the whole household.

And women are also very much involved in selecting seeds. So usually when they have to choose the seeds that they would like to plant for the next season women are involved in this activity because they are also the ones who usually have to prepare food and so they they know which type of characteristics the different crops need to have the they know which beans Cook in less time which have a better taste which are better for some dishes or others or even the importance of some of the varieties for specific traditions or rituals or festivals.

So, the role of women is really is very important in maintaining this diversity within the household and also in ensuring more diversity in the nutrition of the or the household itself.

On Syria

We have been working also on this because the situation in Syria is so dramatic and it’s so terrible and it’s really an extreme example of what can happen to people in a war situation but actually traditional knowledge and local knowledge is being lost all over the world because of globalisation because of a lot of times because of modern technology and so on and so we work towards trying to conserve this.

On documenting recipes

This local knowledge and making sure that is it is transmitted to the younger generation. So, we have programs working with schoolchildren. But we also encourage communities to conserve. For example, biodiversity registries. So they have at the community level and they will keep a registry where they will note down all the diversity that is in their community all the different traits that different crops have and what they use for how they are managed on farm and this information is very important to keep at the community level and to make sure that is it is then transmitted to the younger generations because we also seen a big pro black problem that is that sort of migration to cities so younger generations also eating the agricultural systems to go on and look for jobs in the cities.

But not only agro-biodiversity registries is important to sort of keep track of this knowledge. We also work with the seasonal calendars where communities themselves will list all the different products that they are available during the different season in a year. And together with the name of the crop and the characteristics there is also different information on how it’s used for example.

And we also try to have community members especially women write their own recipe books. So, we have worked a lot in Central Asia with producing booklets that report all the different recipes. We have done this also in Cuba where we have all traditional recipes which are not known at all in the cities. And so this is also a way to keep this this knowledge alive.

On global networks

There are different networks that can be that can be used to share information. I was thinking of one that is the platform for agro-biodiversity research, which is actually hosted year in Bioversity International, and it is a network where anyone who is interested in agro-biodiversity can sort of link to and also put any type of information that they would like to share with other people.

And it’s actually a global network. So, this could be a way to share information. Obviously, language can be a barrier. We tend to stick to English, French and Spanish, but not even always we manage to do translations into French and Spanish. So, language can be a barrier. But I think networks of this type can be a good a good solution. Also, if communities have access to internet because it’s not always it’s not always the case.

On food and urban environments – Cuba

We did have a small program looking at um from rural to urban looking at also gardens and the creation of a vegetable gardens in urban environments. A lot of times we are trying to link the rural sector with the urban ones so that there is a sort of mechanism that products can flow directly from the agricultural sector to the cities.

We have seen for example that in Cuba there is a problem with the food supply and that is basically linked to the fact that transport is very bad there, and farmers are connected to the to the government. So the government cooperatives are other ones who go round the different farms to collect the produce that they want but not all the products are requested. So, a lot of the fruit that is produced, for example, in the farms, is then wasted because there is no market with the government cooperatives.

So that for example we have worked together with the Urban and Suburban Program which in Cuba is very strong, to try to create local markets that actually can be supplied directly by the farmers, and it’s working quite well because people in the cities are actually very interested in getting fresh produce, and also varieties that they are not used to have in the cities.

Living on a farm

In actual fact I have a farm myself. So my husband is is a farmer and we have an organic farm not very far from where where I work. We have seen changes in climate of a very short period of time. I mean we have been we have been cultivating for maybe 15 years and it’s really very difficult to predict what’s going to happen, and to know when you have to plant you your crops because you might have a cold spell, you might have a lot of rain, or it may be very hot and dry so the only way to overcome these problems is actually to have a bigger array of diversity where you can choose from. And so, if you cultivate different types of tomatoes that have that are resistant to two different biotic and abiotic stresses then you might have a better chance of picking some of the tomatoes at the end of the season.

So I mean this is the only way that we can actually go, and I would say that Italy we’re very fond of our food and so we still have quite a lot of connection with the land, and a lot of young people are sort of going back to farming maybe because it’s difficult to find other jobs, a job that that can with which you can actually survive both because you work you can eat your own food, but also because it’s actually there’s quite a lot of requests for fresh organic foods here in Italy. Yes.

Farms in Europe I would say have to differentiate their income so It’s not only farming but usually it’s also a transformation of some of the products, or even restaurants or having school activities. So taking sort of educational plans with schools so schools come to the farm they actually do some experience. They do some work and they and the kids actually see where their food comes from. Yes, this is quite common.

The market has just a certain amount of space and I don’t think everyone can sort of go towards agro-tourism because the market at least here is quite saturated at the moment. Yes.

Diversification is resilience

This idea of diversification is what we also call resilience. And we have been working quite a lot on this with also with other partners around the world. And one of them was the Satoyama Initiative which is an international partnership made up of a lot of different institutes from all over the world, who have come together basically to work on the so-called social ecological production landscapes or seascapes, because the idea of conserving nature without human beings is actually an idea that doesn’t work anymore.

We have seen that all this all the ecosystems of the world have been altered in somehow by human beings. And a lot of these systems have core evolved with human beings. So, they have been shaped by their activities. But they also have to withstand the test of time. So, a lot of these systems are actually still producing and still sustaining the livelihoods of the people working on these systems. What we have tried to do is actually to understand what has made these systems resilient over such a long period of time.

And we have seen that resilience is actually depends a lot both from a social and ecological point of view on the diversification. So, the same definition of social ecological production landscape is in fact of a mosque a mosaic of different land uses and habitats. So, for example village’s farmlands, grasslands, forests, pastoral lands, and coasts that have been for old and maintained through the interaction between people and nature in a sustainable way.

Satoyama Initiative Framework

And we call them Satoyama, we call them social ecological production landscapes. There are other programs that work with these types of systems on a landscape level. Resilience is actually linked to the capacity of these systems to adapt and to change to the changing conditions. But maintaining their sort of main functions and their main structure.

And so as I was saying we have been working with a lot of these type of landscapes and the communities that live in these in these landscapes and we have seen that to increase resilience they need to have a lot of agriculture to maintain a lot of agricultural biodiversity that

Local culture and knowledge is extremely important that also diversification of farming income is increasingly important so that they don’t depend only on one sector and this can be done through ecotourism it can be done through artisanal work or differentiating the sources of income through different types of activities that are ways that still are sustainable for the environment.

And this is why then in the end we developed a series of indicators, social resilience indicators that were actually developed to do this to measure resilience within these systems. But these indicators are a sort of a participatory approach so they are they are mostly I would say qualitative more than quantitative indicators. And it’s the communities themselves that assess the resilience of their own of their own systems, because resilience to them it might be different from what we see as resilient.

They all have their own world views. They have their own aspirations and might see things in a different way. For example, one of the indicators that comes to my mind is that we look at infrastructure within the landscape and often as a Westerner we might think that they lack a lot of primary facilities that for us would be essential like, for example. electric power. But some of these communities are actually interested in different things on electric power for them was not their primary concern.

So it’s interesting to use this this approach because you actually have the communities himself assess what they think and what they see they see as resilient in their system, and then they are able also to work on their landscape and try to improve the resilience through different type of activities.

So, resilience is the capacity to learn and adapt to the changes. So, a system is resilient not when it stays in its own stages for a long period of time it’s not conserving a museum for example but it’s a dynamic there. We’re talking about dynamic systems that change over time. But the capacity to learn and adapt for changes and the base has to be a rich system in biodiversity wild and natural biodiversity. Governance is important within the systems culture needs to be something that we tried to conserve. And those are the sort of the local ways style of life and so on and on and at the same time introducing also technology, I mean we’re not trying to if technology is useful in these situations it’s a good thing.

Equity, participation are absolutely fundamental. Yes.

——————————

REETU SOGANI

My name is Rita Sogani, and I have been living in the in the hills in the State of Uttarakhand in India, for the last 20 years, and have been working very closely with the grassroots community, especially women and that marginalised community on the issue of traditional knowledge systems and practices.

The work primarily is about how to protect and conserve the traditional knowledge systems and practices which exist in the area of agriculture, forest, water, natural resources. How to strengthen the knowledge system, and how to promote the knowledge system as one of the important base of livelihood of people here.

Reetu Sogani with women in the Himalayan foothills.

On what we can learn from traditions

When we talk of traditional knowledge, then what we mean is the knowledge that people have been accumulating, have been experiencing, have been observing, for centuries together, actually.

It’s an oral tradition, you know, which has been handed down the generation, from the one generation to another orally. It’s not documented. It’s not coded.

For example, how to grow or agriculture, in very hilly area which is around 1500 meters or 1500 meters to 1700 meters. The kind of soil that we have here; how to use that soil in growing different kind of crops, how to manage the forest sustainably, but at the same time also use it in such a way that we have it for the generations later on.

That knowledge that people have, is something that they have a have heard their parents or grandparents speak about.

In other words, it’s just common sense.

On gender roles

When I started working the hills in 1998, I had absolutely no idea of what the situation is as far as the local knowledge in the hills is concerned.

I had no idea how it is connected with women and men.

It’s the women actually in the hills who have been very closely connected with the natural resources, be it forest, be it agricultural, be livestock management, be it even health related practices, governed by food items and herbs.

The roles and responsibilities of women are such that they stay in the house, and they carry out all the activities close to the house, you know, which are connected with natural resources. So, agriculture in the hills is not just connected with land, or is not just connected, you know, with growing crops. It’s very closely connected with forest, very closely connected with of course water, very closely connected with livestock.

So, she is the one who is very closely connected with all these sectors, and she is the one who is interacting with them on day to day basis.

She knows what grows where, what leaf should be used if the goat actually has indigestion. Or how the compost is prepared, and how those leaves can be used for the preparation of compost.

So, she is the one who has been interacting with all these ideas, and so she has the knowledge, and she has the skill; first-hand knowledge and first-hand knowledge systems and practices in these sectors.

The role of men in villages

Men definitely they are also contributing in agriculture but only in couple of activities. But of course this is a general picture but men mostly prefer to work outside in the villages, or outside, they migrate to the towns or sometimes they migrate to the main towns like Delhi, Bombay and other places, to bring in money.

In fact, the hill economy is also called the money order economy, where the money actually comes in through this money order or through the check, and many people in the hills have also joined the army.

So, it’s the women who has been associated with agriculture and related areas.

One of the research institutions came out with this figure of 98.5 percent, 98.5 percent of the work relating to agriculture is being carried out by women.

Land and forestry management is in the hands of women. Shown here, the women of Majkhali take compost to the fields.

On women’s view of health

I ask this question from one of the women as to ‘how do you describe health? The word health’

She gave me such a beautiful and different answer.

She said: The animal that you see is still important for health. The kind of crop that we are growing and the methods we are using. That is also connected to the water that we are using. That is also connected with health, what I’m eating and how I’m eating is also connected with my emotional health.

She said, it’s so difficult to describe because all the things around me, are contributing to health, and the air that I’m breathing in, you know, that is also part of health. The forest is responsible. The trees are responsible.

So, she described health in such an integrated and holistic way. That was my first lesson actually.

I mean, if you asked this question from any doctor or any person in the urban area, he or she would say health is the absence of illness. ‘I don’t have any illness.’ How compartmentalised our approach has become, you know in comparison to how people think.

On driving change

And when it comes to women we have to work at various levels. It’s not just at the grassroots level but we have to work at various policymaking levels. Even the grassroots level is very important there, women are not able to make their voices heard even in the local self-governance bodies.

Because of the kind of roles and responsibilities they have they don’t have time, they’re not supposed to be seen in those decision-making forums and processes, because they believe that they’re not supposed to be here. They’re supposed to be doing their household chores.

So that kind of mindset actually has to change, and gender sensitisation has to come about at all levels. Also, at the household level. It’s not something that is very easy, but it’s happening now.

Last year we had a meeting at the state level, in which we had invited the government officials, of not just our state but of the nearby states also, and there were several organisations, Forest department was also there, Agriculture Department was also there- I was so happy to see Parvati who is a wonderful farmer, extremely knowledgeable, spokesperson of our forest Committee, standing there in front of everybody and telling people ‘we want traditional crops we will grow really traditional crops, we will not use any of the chemical fertilisers that you people from promoting because of these, these and these reasons.

On women farmers and land rights

One of the other issues which I have not mentioned actually right now, but which is very closely connected to the women farmers; they are doing the majority of the work related to farming, they are actually not known as farmers. They’re not recognised legally, administratively and even socially as farmers, simply because they don’t have land in their name.

It’s really sad. It’s very deeply sad and very ironical I would say.

If you take into consideration Nepal, India, and Thailand, not even 17 percent of the total landholdings actually belong to women. And these are the areas where women contribute maximum to the agricultural economy.

There is still such a tough battle going, on because the land does not get inherited by women. But it has very serious implications on her work, on her capabilities, or no capacity building, on his skills.

Because she is not recognised as farmers, it’s only men who are being invited to the workshops by the government, by any other organisation. Women don’t have access to credit. They don’t have access to the government.

The first thing they ask for is to have the land title in your name, and with increasing migration, and reduced access to resources, the condition of the women has actually worsened over the years, I would say.

We have a big network. This is called Mahela dichotomous that is ‘women farmers rights’. And we are doing everything possible to influence the government, to change the land inheritance rules to include women, which will take many, many years because land is a very important source of power.

But at the same time at least I recognise them as cultivators. At least recognise them as cultivators — at least give them the right to be able to access the bank, and access the credit, whenever they want to.… to access the government, the schemes, the government schemes should not be asking only for the land titles but they should be asking the name of the cultivator. I think it’s very much possible.

This is making the life of the woman very difficult and it has made the situation worse actually over the years because with the decision making vested in absent men, it becomes so difficult to make good important decisions at the right time.

Work relating to agriculture continues to be done by women, but without any decision making it becomes difficult for her, you know, to carry it on for her. Pretty frustrating, very frustrating.

Systemic sexism – an example of administrative failure

One of the women from our area she had gone to the bank and she was just filling up one form. I think she was opening an account and there was this column that said what is your profession?

She wrote farmer, and the bank officials refused to accept it. He said “You are not a farmer, you are a housewife.”

She had the understanding, she had the business, and also some confidence when she was with other women also there. She said: “I’m a farmer, you have to put down my name because I’m the farmer, I’m the one who is tilling the land, I’m the one who is cutting, I’m the one who is weeding, I’m the one who is harvesting, how can you not call me a farmer. I will not delete the word farmer.

I will continue to use the word farmer. He had to accept it. He did accept it! She was only opening a bank account.

The gender sensitisation hasn’t taken place at that level. So that’s why I’m saying administratively she is not recognised as farmers.

She is still considered to be somebody who is carrying out only the household chores. Her unpaid work; be productive, or be reproductive, or be it caring responsibility, is not being recognised, it is not visible is not being acknowledged.

Here, widows get the right to land title, once their husbands pass away, you know. Parvati also mentioned this in that meeting, in the keynote speaker speech. She said “As long as a husband alive, you know, we have no right over land. Only when he dies, when he passes away, only then we are allowed to have the right over land.”

It hit them really hard. Even the rule which is in favour of them in an actual reality they’re not recognised not just legally but also administratively. It’s the structural change you need to bring about. It’s just that it is the system which responsible for this state of affairs. It is connected to globalisation.

On the film created by the Climate Development Knowledge Network

The biggest NGO working globally. On climate change. Climate Development Knowledge Network, made a film on these women who are part of our group, and the title of the film I think is ‘Missing Women in Decision Making’ and these very women video recorded themselves, as to what they’re doing, how they’re doing, how it is connected with climate change, how it is actually helping them mitigate, how it is helping them adapt themselves.

Women with me have gone to Malaysia and in Malaysia they have spoken about these very things, they have shared their experiences their opinion their needs, their priorities, everything.

We have settled myopic way of looking at things, interconnectedness with nature.

This is what interconnectedness is.

I mean it’s not about just interdependence it’s also about cooperation. People are interdependent. But more than interdependence there is this cooperation, amongst these then villages of the micro watershed around these sectors.

View of Mountains from Majkhali Village, The Vrikshalaya Centre.

Traditional knowledge is not just about technique. It’s not just about practices. It’s about a very integrated interconnected interdependent system you know, which runs through people’s cooperation, which again actually is on the decline.

The social cohesion, the value for the simplicity, you know, the value of the equilibrium all these values, they were very, very integral part of our traditional system, or way of life. And all of these values they make people more resilient. Social cohesion was such an important aspect of people’s lives fiscally those were more modern life like for example.

Diversifying crops

We have a practice in the hills called Palta, P A L T A (spells it out) — which means that people contribute in each’s labour.

People from not just my household, would contribute, but people from the other households in my village, would contribute, as well as from other villages also.

And the same would happen, I would go and contribute, my whole day, the entire day you know. In carrying out that activity. And this would help mostly those people single women. Women whose husbands or who’s the men folks have migrated, but they’re not… they’re not…there. And the elderly couple households.

So social resilience and social cohesion and all these values actually increase people’s resilience. But unfortunately, that kind of agriculture that we are following now makes people very individualistic.

What we need to do

I think one of the important things that we have to do is do to have our resources to have belief in our resources, and to strengthen the existing biological diversity, and the cultural diversity, whatever little remains of it.

It’s not that it’s impossible because I worked in certain areas in the hills for the last ten years twelve years and people have changed. I mean they have brought about changes in their food diet, they have brought about changes in their agricultural system. And we are not going to those areas anymore.

The experience that they have already you know, and the awareness that they have is enough actually to last for a very long time. And also, it could get transferred to their children. They’re also growing cash crop, but at the same time they’re also getting finger millet.

They are buying things from the market but at the same time they have their agriculture to fall back on.

On biodiverse farming

Biodiversity based ecological farming, mixed cropping system, done organically– They can also produce much more, not just equivalent to chemical intensive farming. This is one great disbelief that people have, the government have, is that chemical intensive farming can feed the mouths of the increasing population, and organic farming can’t.

This is all wrong actually, and so many studies are there to prove it otherwise. I would not call it organic farming, but biodiversity based, ecological farming. In balance with the nature.

Because organic farming can also promote mono cropping which is happening actually.

Organic farming is just one component of biodiversity based ecological farming. When it comes to chemical intensive farming of course, the adverse impacts are quite well known, and even the government of Uttarakhand and other state governments are not promoting chemical intensive farming anymore, but they are promoting organic farming.

We are talking about biodiversity, also, you know in the farming and the ecological farming

keeping in balance you know with the ecology the surrounding ecology, which is most important.

On organic farming

Organic farming can also promote mono cropping. Organic farming only talks about cropping system which is minus chemicals, minus synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

That is one important component of the farming system that we are talking about, but we are also talking about mixed cropping system, which would take care of the health of not just the soil but also of course take care of the health of the livestock and also take care of the health of the human beings, because it will ensure availability and access to food and nutrition at all things of the year.

On the practice of 9 crops

We have a practice of growing nine different kinds of crops in one single season during the rainy season. And these different crops are about Grains, Spices, Oil seeds, different pulses, all these nine different kinds of crops would grow in one single field, in one single season and it will get harvested of course at different times of the year but it will ensure availability of some food you know in the household at any time of the year.

Now the studies have also proved that both of us based ecological farming on mixed cropping system done organically will take care of not just the production but also of the health aspect.

We have the studies and we have the data that can prove, you know, that their production can be higher than the production of mono cropping. Done just next to that field.

On nutrition

The amount of nutrition which is coming out of that one acre of land and it’ll be much more in comparison to the mono cropping which is growing this next that the one acre of land in one year it is able to absorb two thousand pounds of carbon in a year. Where are doing mixed cropping organically. In comparison to chemical intensive farming which actually releases 300 pounds of carbon per acre, per year.

Considering the global warming which is taking place, it is very, very important to also come up with ways for mitigation; mitigating strategies are much more important and unfortunately nobody talks about it because it is connected with again you know big corporations.

It is connected again with fertiliser companies and nobody is invested in mitigation right now.

Nobody is talking about agriculture which is a very big contributor of carbon emission but can be a very important strategy to sequestrate the carbon, prevent it from emitting, and also absorb the carbon which is in the atmosphere.

Agriculture done this the mixed cropping done organically is considered to be the only way through which we can do carbon sequestration at a very fast rate.

This is in total contrast to the policies of the government which is talking about monoculture, growing only pine trees in the forest area, and also promoting mono cropping.

I think we have to have a very multi-pronged approach you know, the statistics are also important in certain areas, and case studies are equally important.

Transplanting rice in Majkhali

The job of convincing men…

The village women I had been working with constantly since 2001. They already had been a witness. They had some difficulty to convince the menfolk actually at the household level.

But gradually they interacted with a mentor also and they also started coming to our meetings. We made them interact with few people who have never switched over to chemical intensive farming and make them use their experiences.

We did workshops for them. He showed them video films we showed them many educational documentaries. We took them out on educational trips to some people renowned people who have been working on saving seeds for many, many years. Made them interact with other groups also working on these issues.

We took a walk actually for five days through different parts of Uttarakhand, and they interacted the different communities they exchanged you know their experiences, they heard about their experiences, and gradually they finally got the confidence to do what all of us had been talking about.

They shifted from chemical intensive farming, to gradually organic farming and the mono cropping to mixed cropping. Surrounding villages have also actually turned, after having seen them you know after having heard their experiences, they have also gradually turned organic, and they have also gone back you know to those mixed cropping systems, through their interaction so they have become kind of leaders actually in all the.

The government of Uttarakhand declared itself organic many, many, many, many years ago but it has not created any market where farmers can actually sell it organic produce. That’s a big challenge too. It’s not that they have no idea. It’s not that they have no awareness. They know that that middle person actually the takeaway a major chunk of profit, you know, and the farmers are not able to reach the market.

That struggle is still going on, but at the same time in parallel, there are women’s federations and they are selling them now in the market to different outlets. And do value addition packaging, labelling, everything and then sell in different outlets.

This could be the government outlet as well as some other private outlets.

That is happening and that is adding to their income.

They’re also catering to the urban taste you know by having single malt cake or finger millet biscuits. Over the last two three years their children have started offering this local produce.

The things that they were used to eating from outside.

I think in India we have the civil society is quite strong, and the women’s groups are also very strong.

Self autonomy

To self-reliance self-confidence and self-esteem; these are all connected.

So we can’t say that everything in the name of knowledge, which we have inherited, which has come down the generations. is good and very effective. Many of the things that are effective but some of the things are not very effective. Maybe because the situation has changed now, so a good amalgamation, a very balanced amalgamation of local knowledge with the new knowledge also needs to be done from time to time, now, to address people’s emerging needs and requirements.

The most important thing in the amalgamation is: Who is controlling the knowledge? The point of control. It has been a gradual dependence of people on the market. Self-reliance Self Sustenance. Has. Been replaced with total dependence. And that actually has an impact on the self-confidence and self-esteem of people. When we talk of local knowledge. And the replacement of local knowledge. People lose out on this self-confidence the self-esteem and self-reliance.

You should be looking like us it could be an institution it could be a country it could be a civilization, could be a region it could be a section of community it could be market, and a particular section in the market, and it could be an advertising agency who wants you to look like people they are advertising.

We lose identity we lose address we lose the language we lose our food we lose our systems we lose our knowledge we lose their practices and we lose ourselves completely. Lose autonomy, lose autonomy, lose our freedom.

END

——————————————

CREDITS

Thank you for listening to this episode of Nordic By Nature, ON KNOWLEDGE. You can find more info on our guests and a transcript of this podcast on imaginarylife.net/podcast

You can contact Nadia Bergamini via BioversityInternational.org.

Reetu Sogani would like to thank the women of Chak dalar and Chama chopra in the Bheerapani area, in Nainital district. The women in Talla Gehna in Nainital district. And the women in Tola area in Almora district.

She would also like to say thanks to the Chintan international trust-India.

Nordic by Nature is an ImaginaryLife production. For more inform The music and sound has been arranged by Diego Losa. You can find him on diegolosa.blogspot.com

Please help us by sharing a link to this episode with the hashtag #tracesofnorth and follow us on Instagram @nordicbynaturepodcast. We are also fundraising on panteon.com/nordicbynature.

If you are interested in nature-centred mindfulness please see foundnature.org to read about Ajay Rastogi and the Foundation for the Contemplation of Nature. You can follow the Foundation on Facebook, and on Contemplation of Nature on Instagram.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on our podcast.

Please email nordicbynature@gmail.com